Science of best practices

Physics seeks the simplest theory that describes the most phenomena. Software engineering has its own empirical wisdom—KISS, DRY—but we treat these as folklore rather than derivable principles. What if they have a formal basis?

We’ve seen this pattern in other fields. Planes were built from empirical knowledge before aerodynamics formalized the principles, which then led to jet propulsion. The same potential exists for software: all well-established best practices can be derived from first principles.

Categories

The mathematical basis of software engineering lies in category theory—not the complex parts, but the most basic and simple subject. I’ll approach the general topic of formalization from that. To start, let’s explore categories just a bit.

Category theory is a theory about categories, and categories are nothing more than a bunch of objects connected with arrows.

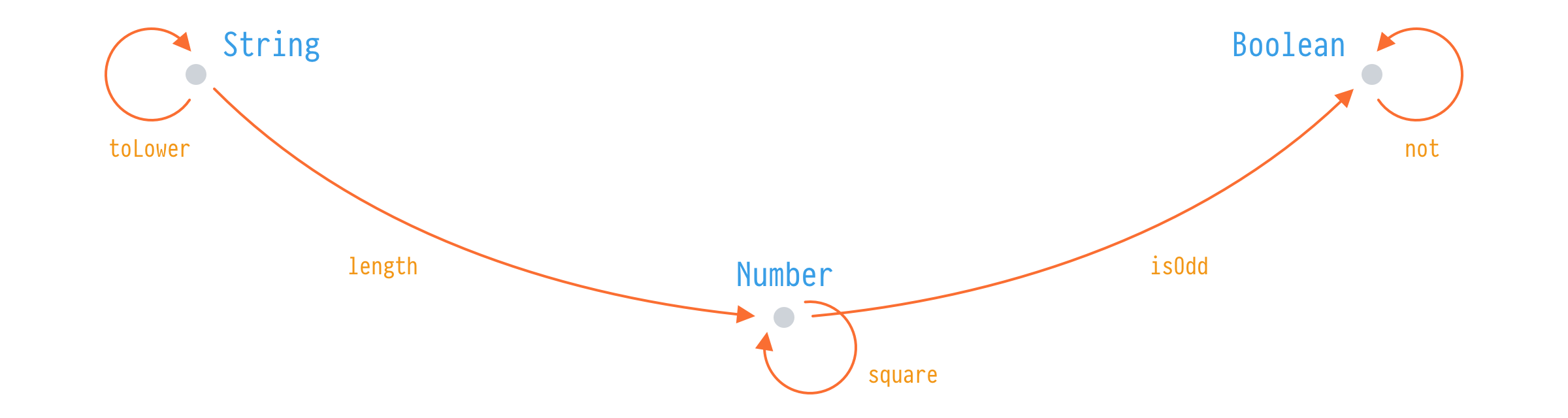

In software engineering, we’re interested in a specific kind of category that is called a category of types. In a category of types, objects are actual types and arrows are functions between them.

In this simple definition, we can make an observation that objects aren’t relevant, they are just there to mark the start and end for the arrows. And if translated, types don’t matter in a category, arrows do. Types are here for functions to have input and output. It’s also not important how many arrows we have between objects. If we have 1, 2, or Infinity everything stays the same.

If we combine this observation with another great idea, we will have enough for rudimentary analysis. That other great idea is the composition.

Composition

In category theory, composition is the ability to derive a direct arrow between two objects when those objects are connected with indirect arrows.

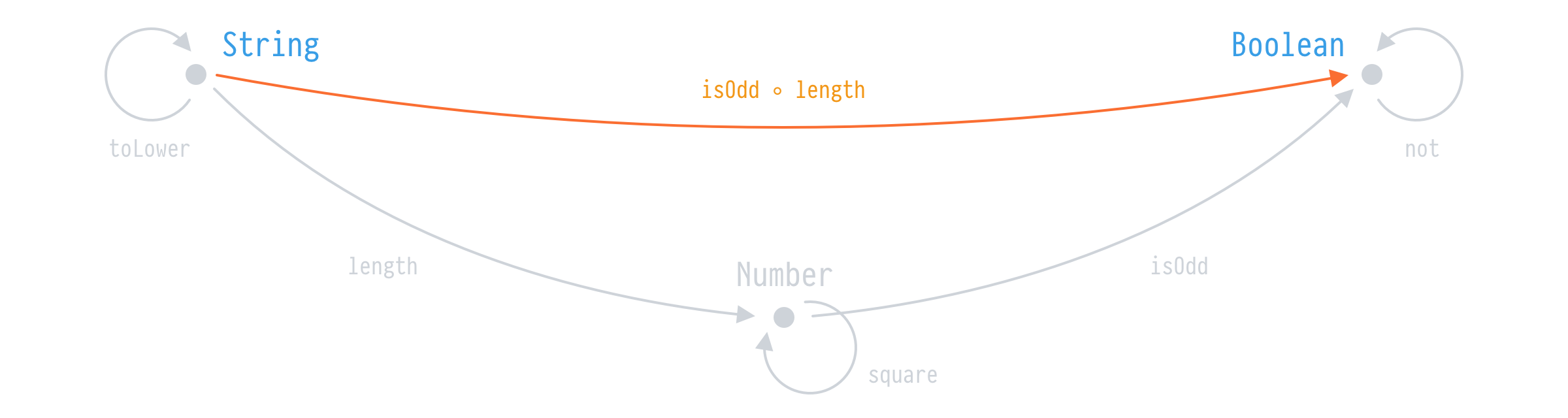

If we have the arrows length and isOdd between String, Number, and Boolean, we can compose these arrows to get a direct arrow isOdd ◦ length. That’s the composition. Note however two rules:

length ◦ isOdd != isOdd ◦ length

length ◦ toLower = lengthWith composition established, we have the tools for analysis. These principles apply to all paradigms—functional languages simply use notation closer to the math.

Keep it simple, stupid

Or KISS. The problem with KISS is that everyone understands “simple” differently. Can we define it precisely? Yes.

Watch how rearranging the same four functions changes what we can derive for free.

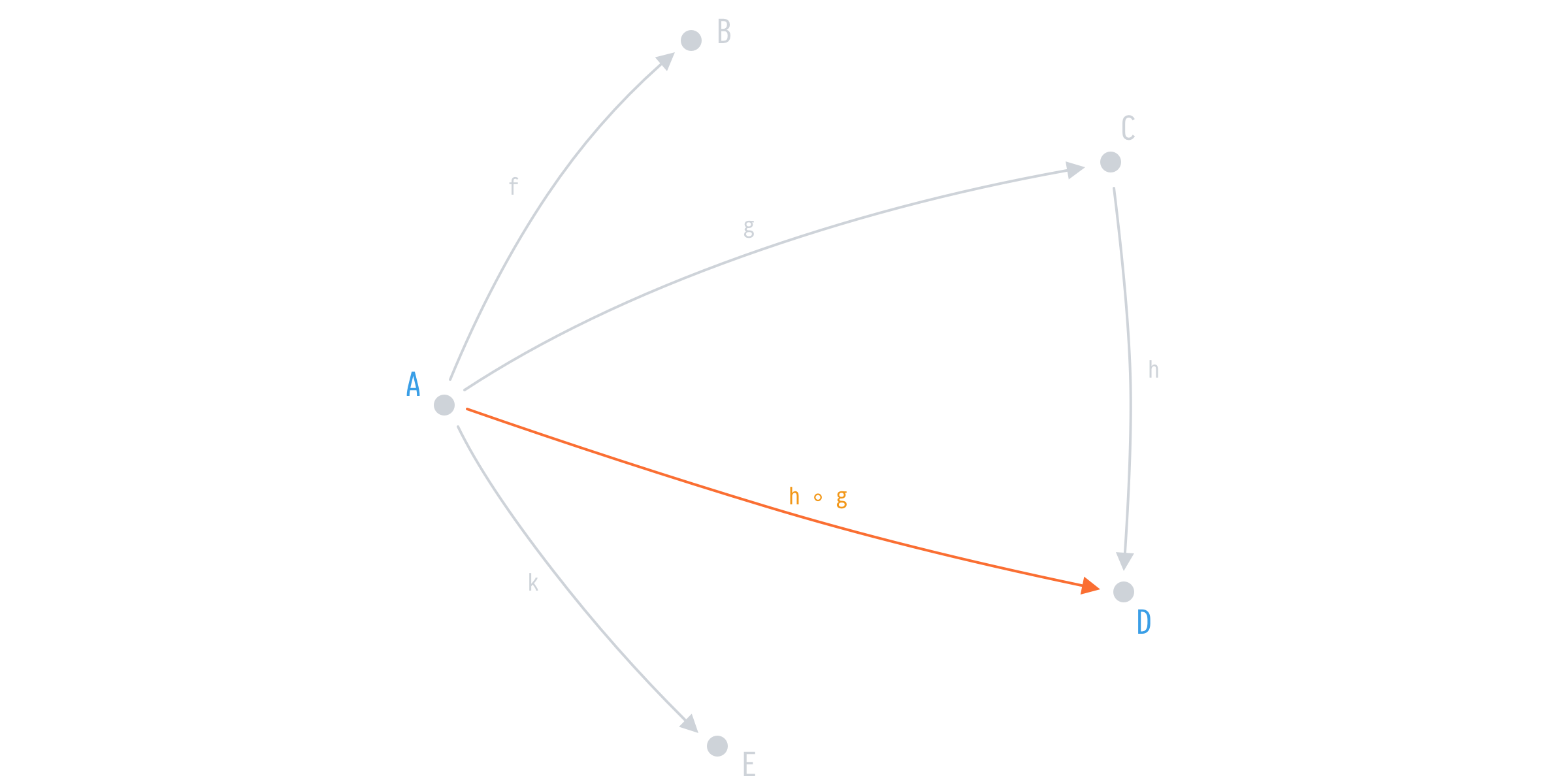

Let’s say we have a simple application with five types and four functions:

f: A -> B

g: A -> C

k: A -> E

h: C -> DIn this category we have one point of entry (A) and ability to map from that point to others via functions f, g, h, and k. However, we can do even better when it comes to mapping from A to D, we can compose h after g and map those types directly.

h ◦ g: A -> DIn a sense, we’ve got h ◦ g for free. And thus are able to easily map from A to D when and if the need comes, say with the next sprint, once your Product Owner decides to show user’s (A) invoices (D) based on their payments (C).

But can we write this program in any better way? In a way that it would be easier to modify it, built on top of it? Sure, we can do that too.

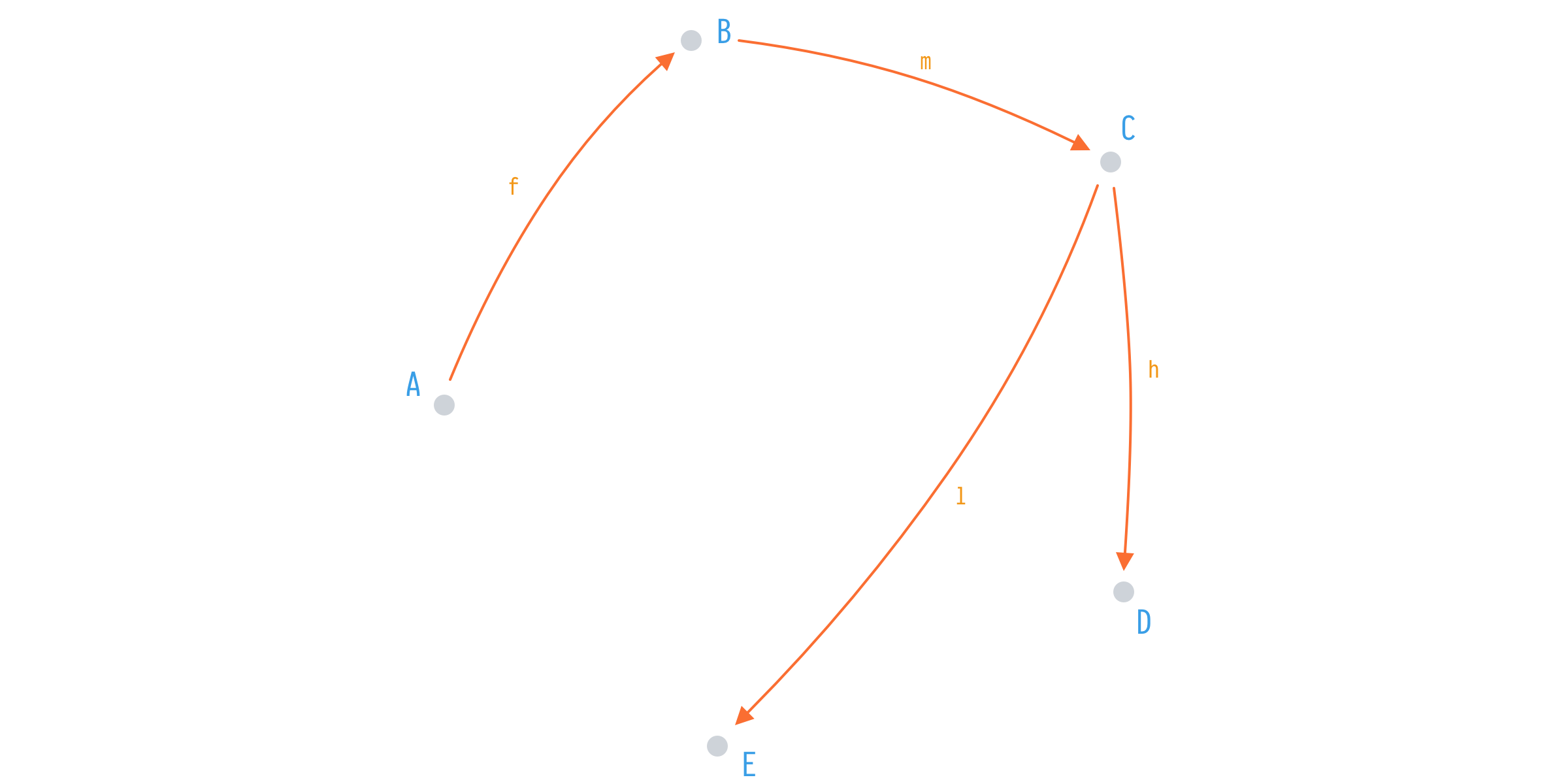

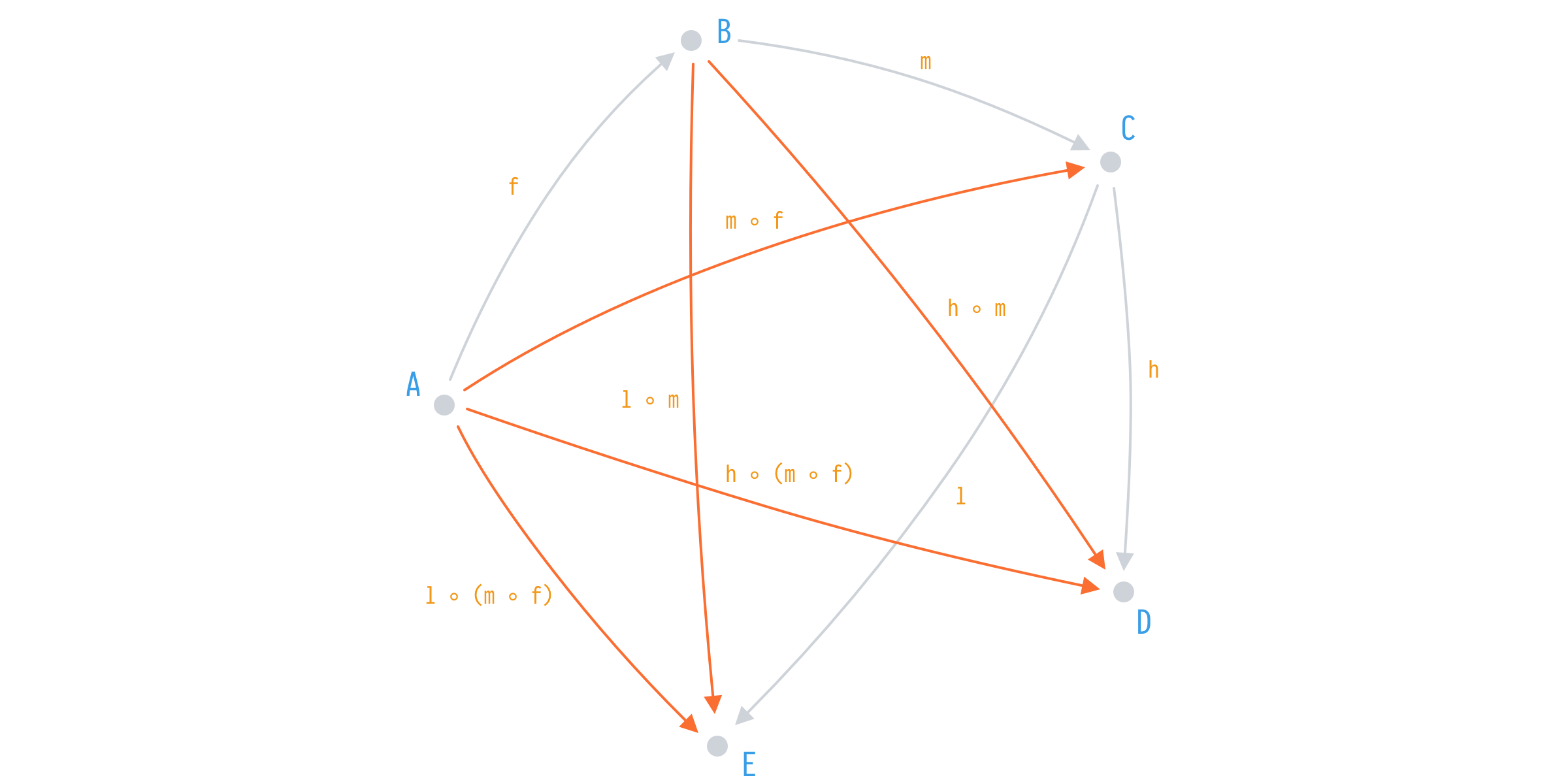

Say, we start with the same types and same number of functions but arranged differently

f: A -> B

m: B -> C

l: C -> E

h: C -> DWe’ve replaced g and k from the first implementation with m and l and at the moment it seems we’ve lost the ability to map from A to C, and from A to E respectively. But hey, we have a composition.

The same number of initial functions on the same objects gives rise to a much more sophisticated system in which we have derived 5(!) new functions. That’s 4 more than what we’ve achieved with the previous example.

m ◦ f: A -> C

h ◦ m: B -> D

l ◦ m: B -> E

l ◦ (m ◦ f): A -> E

h ◦ (m ◦ f): A -> DSame functions, same types—but the second arrangement yields 5 compositions versus 1. We even recovered g as m ◦ f and k as l ◦ (m ◦ f).

This makes simplicity measurable:

Simpler functions in a given application are those that can be composed in more ways than others.

This definition makes simplicity objective and countable rather than a matter of taste. Given a function a that produces 10 compositions with the rest of your application versus two functions b and c that together produce 20 compositions—the pair is simpler despite having more parts.

What’s next?

DRY follows similar reasoning—it formalizes as beta-equality from lambda calculus, where duplicate expressions can be factored into shared bindings. But that’s for another article.

The larger point: best practices aren’t folklore. They have mathematical foundations, which means we can derive new principles rather than waiting for empirical wisdom to accumulate.